Designed by Paul Smith 2006. This website is copyrighted by law.

Material contained herewith may not be used without the prior written permission of FAUNA Paraguay.

Photographs on this web-site were taken by Paul Smith, Hemme Batjes, Regis Nossent, Frank Fragano,

Alberto Esquivel, Arne Lesterhuis, José Luis Cartes, Rebecca Zarza and Hugo del Castillo and are used with their permission.

Myrmecophaga tridactyla Linnaeus 1758 Image Gallery

TAX: Class Mammalia; Subclass Theria; Infraclass Eutheria; Magnorder Xenarthra; Order Pilosa; Suborder Vermilingua; Family Myrmecophagidae; (Myers et al 2006, Möller-Krull et al 2007, Gardner 2007). The genus Myrmecophaga was defined by Linnaeus in 1758. The genus name Myrmecophaga is from the Greek for "anteater". The species name tridactyla means "three fingers", distinguishing it from the "four-fingered" Tamandua, the only other living species. Gardner (2007) tentatively recognised three subspecies, M.tridactyla tridactyla being present in Paraguay. Synonyms adapted from Gardner (2007):

[Myrmecophaga] tridactyla Linnaeus 1758:35. Type locality “America Meridionali”, restricted to Pernambuco, Brazil by O.Thomas (1911).

[Myrmecophaga] jubata Linnaeus 1766:52. Type locality “Brasilia”.

M[yrmecophaga]. iubata Wied-Neuwied 1826:537. Incorrect spelling.

Tamandua tridactyla Matschie 1894:63. Name combination.

Falcifer jubata Rehn 1900:576. Name combination.

Myrmecophaga centralis Lyon 1906:570. Type locality “Pacuare” Limón, Costa Rica.

Myrmecophaga trydactyla Utrera & Ramo 1989:65. Incorrect spelling.

ENG: Giant Anteater (Gardner 2007), Great Anteater (Lyon 1906).

ESP: Oso hormiguero (Neris et al 2002, Parera 2002), Tamanduá bandera (Carol Fernández pers. comm.), Oso bandera (Neris et al 2002).

GUA: Jurumi MA (Neris et al 2002, Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Yurumí (Parera 2002), Tamandua guasu A (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Kuarevachú Ac (Villalba & Yanosky 2000), Jautare P (Villalba & Yanosky 2000).

DES: With a long tubular head and tiny, circular toothless mouth, the Giant Anteater is like a living "vacuum-cleaner". The extensile tongue is some 60cm long and cylindrical, and secretes a sticky substance that traps their prey. The head is merely an extension of the snout and bears small, relatively ineffectual brown eyes and tiny ovaloid ears that do not emerge above the level of the head. The legs are robust and powerful, the front feet bearing five toes including three viciously-hooked claws, so well-developed that the animal must walk on its knuckles. The other two toes are greatly reduced. The hindfoot also bears five, more reasonably-sized claws, enabling the animal to correctly use the sole. There is a slight hump at the base of the neck and a line of stiff hairs along the midline form a bristly mane. The pelage is long and stiff, mainly greyish peppered with white and with a broad black band stretching from the throat forming a triangular point at the shoulder and bordered thinly with white along its length. The forelegs are mostly white with large black patches just above the forefeet. The hind legs are mostly black. A voluminous bushy grey tail greatly exaggerates the size of the appendage. CR - Occipitonasal length 210mm. Elongated rostrum with nasal bones of similar length to the frontal bones. (Díaz & Barquez 2002). DF: I0/0 C0/0 P 0/0 M 0/0 = 0. CN: 2n=60.

TRA: Forefoot completely different to hindfoot, showing traces of two large claw marks on outer part of print. Hindfoot somewhat rounded and only slightly oblong, with five, relatively short, even-sized toes. Does not leave trace of tail. FP: 10.8 x 9cm HP: 8.6 x 6cm. PA: 11cm.

MMT: TL: 182-217cm; HB: 126.5cm (100-140cm); TA: 73.4cm (60-90cm) plus hairs of c30cm in length; FT: 16.5cm (15-18cm); EA: 4.7cm (3.5-6cm); WT: 31.4kg (18-52kg); WN: 1.5kg (1.1-1.6kg). (Parera 2002, Neris et al 2002, Nowak 2001, Emmons 1999, Redford & Eisenberg 1992).

SSP: Unmistakable on account of its size and colouration. Only Tamandua tetradactyla has the same basic shape, but it is creamy-yellow in colouration not black, considerably smaller, lacks the bushy tail and is semi-arboreal in behaviour. Footprint of Tamandua has a trace of a single hooked claw and rounded pad on forefoot and hindfoot more elongate (almost twice its width) with longer toes. Tamandua drags the tail along the ground leaving an imprint in soft substrate.

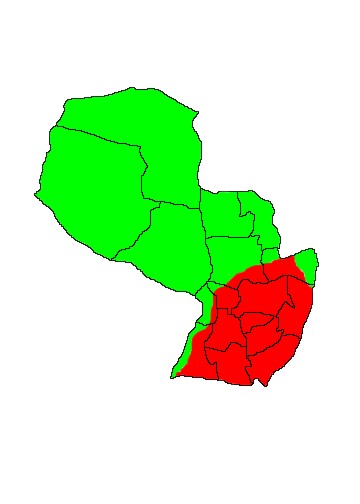

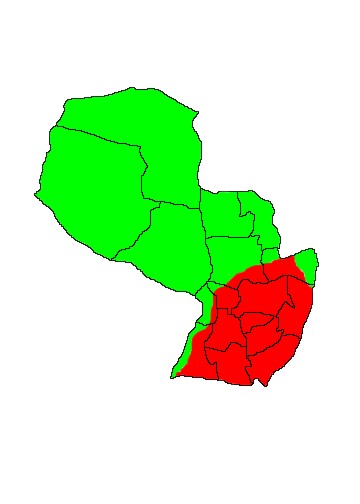

DIS: Widely distributed from Belize and southern Central America (where it is disappearing), through much of South America (except the Andes) and south to Santiago del Estero in Argentina - though historically it ranged as far south as 31ºS. It is extinct in Uruguay. In Paraguay it occurs throughout the country but has disappeared from large areas of eastern Paraguay as a result of hunting pressure. (Neris et al 2002, Parera 2002). Three subspecies were tentatively recognised by Gardner (2007). M.t.centralis Lyon, 1906 is found in central America south to northwestern Colombia and northern Ecuador. It is absent from western Colombia. M.t.artata Osgood, 1912 is found in northeastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela north and west of the Mérida Andes. The nominate subspecies M.t.tridactyla (Linnaeus 1758) occurs in the rest of the South American range east of the Andes fromVenezuela and the Guianas south to northern Argentina.

HAB: Giant Anteaters can survive wherever there are sufficient ant or termite populations to sustain them, but though they do occur in Chaco forest and in humid forest, it appears to be suboptimal habitat and they are less common there than in open habitats. Large areas of suitable grassland and cerrado habitat are present in eastern Paraguay, but they have disappeared from the majority of these areas due to hunting pressure. They are most abundant in the seasonally-flooded palm savanna of the Humid Chaco. Habitat choice is apparently unaffected by fire, a study in the cerrado of Mato Grosso, Brazil finding that they utilised burnt areas as frequently as they do unburnt areas when foraging (Prada & Marinho-Filho 2004). Burning is of course a natural occurrence in the cerrado biome and does not directly affect the species main prey items.

ALI: Giant Anteaters are strictly myrmecophagous and epitomise the concept of sustainable harvest, moving around their territory and visiting ant nests and termite mounds without ever completely destroying the colony or exhausting the resource. Their vision is poor but they overcome that by establishing a routine that helps familiarise them with their territory and by possessing a strong sense of smell which is used in food location. In Argentina termites such as Nasutitermes and Cornitermes and ants such as Camponotus, Iridomyrmex and Solenopsis are preferred with the percentages of each species varying throughout the year (Parera 2002). In the Pantanal of Brazil they consumed only two species of termites (Nasutitermes coxipoensis and Armitermes sp.) and only during the month of June. The same study recorded five ant genera in the diet Solenopsis (46%), Camponotus (12%), Labidus (2%), Odontomachus (2%) and Ectatomma (2%). (Medri et al 2003). They may consume as many as 30,000 individual ants, larvae and cocoons in a single day (Nowak 1991). Ant and termite nests are broken using the hooked claws of the forefeet and the extensile tongue is inserted (reaching some 40cm beyond the mouth but only 10-15mm wide at its widest point), the insects becoming stuck to the mucous-like covering of the tongue or fastening onto it with their jaws. The animal is able to withstand only a short period of feeding before the defensive response of the ants becomes more organised, and it then retreats, ensuring that the colony is not totally destroyed and remains to be exploited at a later date. Braga de Miranda et al (2003) reported on an individual that had apparently raided and eaten a honey bee nest Apis mellifera located inside a termite mound 1.5m high but this is apparently an extremely rare occurrence. The salivary glands of Giant Anteaters appear to be active only when feeding. In captivity the species is raised on a mixture of milk, eggs, mealworms and ground beef, and captive individuals have also taken eaten fruit (Nowak 1991). Giant Anteaters drink frequently and when the water table drops below the surface they may even dig to access water sources, in the process habilitating them for other mammal species (Emmons et al 2004).

REP: Pair comes together only for a brief courtship period between May and July and a single young is born after a gestation of 183-190 days (6 months) - though births after as little as 142 days have been reported (Nowak 1991). Newborns have the eyes closed but they open after 6 days. Young are weaned at four to six weeks but are carried on her back "piggy-back" style for up to a year, ensuring that the black-and-white shoulder band is aligned with that of its mother to help break up its body shape (Parera 2002). Occasionally juveniles may be left in a "nest" while the mother feeds. Juveniles remain with the mother until she becomes pregnant again. Giant Anteaters reach sexual maturity at 2.5 to 4 years. (Neris et al 2002).

BEH: General Behaviour For the most part solitary and diurnal in behaviour, Giant Anteaters revert to being nocturnal only in areas where they are persecuted or human activity is high. Most activity takes places during the early hours or the morning, but activity takes place throughout the day on cool cloudy days and during rain when temperatures are lower. They are territorial and the home range is generally quoted as 9 to 25km2 (Neris et al 2002) though in Argentina 3 to 90km2 has been suggested (Parera 2002). In Brazil territory sizes of 3.67km2 for females and 2.74km2 were recorded (Shaw, Machado-Neto & Carter 1987) - though the difference is not statistically significant. Territories frequently overlap, but individuals keep their distance from each other. Shaw, Machado-Neto & Carter (1987) recorded an overlap in territorial range of 29% in females but just 4% in males, reflecting their more aggressive character towards conspecifics. Giant Anteaters are surprisingly capable swimmers and can cross wide rivers but do not climb trees (Nowak 1991). Emmons et al (2004) documented the bathing behaviour of Giant Anteaters, noting that they did so during the night but were unable to reach a conclusion as to why the animals bathe given that they do not fit the profile of typical bathing mammals. They did however add that captive animals apparently enjoy being hosed down and even aggressively compete for spaces under the spray. In general they walk slowly with a lolloping gait, but are capable of running at high speeds if disturbed (Emmons 1999). Though clearly capable of digging they do not construct burrows to sleep, preferring to curl up in a secluded area with the head between the forelegs and the huge tail curled over the body. A captive individual lived for 25 years and 10 months (Jones 1982), but a life expectancy of around 16 years is considered normal for captive individuals (Redford & Eisenberg 1992). Aggressive Interaction Males are more aggressive than females and the majority of agonistic interactions occur between males. Such interactions range from slow circling to chases and even fighting which can result in serious injury. During one such encounter observed by Rocha & Mourão (2006) in the Brazilian Pantanal one individual apparently detected another by smell and began to walk towards it giving a long, drawn-out harrr noise. The two animals circled each other with tail raised before the aggressor began to strike at the other´s face with his foreclaws. After a few seconds the attacked animal fled and was chased over a distance of 100m by the aggressor who maintained the tail raised. A captive group of three males and two females lived apparently in harmony at Sao Leopoldo Zoo in Brazil, but such group living has never been recorded in the wild (Widholzer & Voss 1978). Defensive Behaviour Though almost blind and comparatively slow moving, it would be a mistake to think that the Giant Anteater is defenceless. For the most part they are tame and approachable creatures and bear no threat to man, but the vicious hooked claws of the forefeet are as efficient at ripping open the skin of attackers as they are at ripping open termite mounds. Typically the animal will react violently only when cornered, rearing back on his hind legs and hooking with the forelegs in the direction of the intruder. Human fatalities in the wild state are almost unheard of, but a zoo keeper was killed by a captive Giant Anteater at the Florencio Vela Zoological Park in Berzategui, Argentina on 10 April 2007 after suffering massive injuries to the torso and legs. The previous keeper had resigned because of the animal´s aggressive temperament. (En Linea Directa News Report April 2007).

VOC: Adults are usually silent but on occasion produce quiet grunts, especially when perturbed. A long, drawn-out harrrr sound was given by an individual approaching another prior to an aggressive encounter in which the other animal was seriously injured (Rocha & Mourão 2006). Juveniles give sharp whistles to keep contact with their mother. (Emmons 1999)

HUM: Because of its large size, predictable behaviour patterns and cumbersome movements this species is an attractive target for hunters and it figures in the diet of various indigenous groups (Cartés 2007). However the religious beliefs of the Chamacoco Indians of Departamento Alto Paraguay prevent them from consuming the meat of this species (Neris et al 2002). Various parts of the body have supposed medicinal properties. Burning of the pelage creates a smoke that when inhaled cures bronchitis, whilst the ash generated from burning tail hair heals wounds and doubles as a contraceptive. Bones are considered an alternative medicine for rheumatism and fat is used as an ointment to prevent over-exertion of muscles during pregnancy. (Neris et al 2002).

CON: The Giant Anteater is considered Lowest Risk, near threatened by the IUCN, click here to see the latest assessment of the species. It is listed on CITES Appendix II, click here to see the species account in the CITES Species Database. In eastern Paraguay it has disappeared from large areas of suitable habitat and does not tolerate well the presence of humans. Being slow and short-sighted it is an easy victim for hunters and local extinctions have occurred in most departments and it appears to be decreasing in most areas of the Orient where it still occurs. It remains common in the Chaco (particularly the Humid Chaco and Pantanal) where population pressure is low and vast amounts of pristine habitat remain. However they are frequent victims of roadkill on the Ruta Trans-Chaco, with a total of 12 roadkill adults counted along the length of the Ruta on 12 October 2007, easily the most numerous victim amongst the large mammal species (Paul Smith pers. obs.). In a study in Brazil a total of 54 individuals were killed on a single stretch of road between the cerrado and Pantanal over the course of a year, reflecting the vulnerability of this species to vehicles (Parera 2002). Though uncontrolled fires do not affect the availability of food for the species, it does destroy available refuges limiting their attractiveness. Burning of campos to generate regrowth for cattle ("limpieza") is a common practice throughout the year, though historically ranchers observed a "burning season" which had a reduced effect on populations of this species. The intoxicating effects of smoke on this slow-moving animal and its highly-flammable pelage also increase its vulnerability to fires and individuals have been known to burn to death (Redford & Eisenberg 1992) but vulnerability to fire would seem to be correlated to the intensity of the blaze (in turn related to the combustability of the vegetation), and regular burning may in fact be less damaging to the species than infrequent but more severe fires. Burning does not apparently affect the species choice of habitat, it being equally as frequent in burned areas as unburnt areas in the cerrado of Brazil (Prada & Marinho-Filho 2004).

Citable Reference: Smith P (2007) FAUNA Paraguay Online Handbook of Paraguayan Fauna Mammal Species Account 2 Myrmecophaga tridactyla.

Last Updated: 31 January 2009.

References:

Braga de Miranda GH, Guimarães FH, Medri IM , Vinci dos Santos F 2003 - Giant Anteater Mymecophaga tridactyla Beehive Foraging at Emas National Park, Brazil - Edentata 5: p55.

Cartés JL 2007 - Patrones de Uso de los Mamíferos del Paraguay: Importancia Sociocultural y Económica p167-186 in Biodiversidad del Paraguay: Una Aproximación a sus Realidades - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Díaz MM, Barquez RM 2002 - Los Mamíferos del Jujuy, Argentina - LOLA, Buenos Aires.

Emmons LH 1999 - Mamíferos de los Bosques Húmedos de América Tropical - Editorial FAN, Santa Cruz.

Emmons LH, Flores LP, Alpirre SA, Swarner SJ 2004 - Bathing Behavior of Giant Anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) - Edentata 6: p41-43.

EnLineaDirecta 14 Abril 2007 - News Report http://enlineadirecta.info/nota-21777-Un_oso_hormiguero_mata_a_su_cuidadora.html

Esquivel E 2001 - Mamíferos de la Reserva Natural del Bosque Mbaracayú, Paraguay - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Gardner AL 2007 - Mammals of South America Volume 1: Marsupials, Xenarthrans, Shrews and Bats - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Jones ML 1982 - Longeivty of Captive Mammals - Zool. Garten 52: p113-128.

Linnaeus C 1758 - Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species cum Characteribus, Diferentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Decima - Laurentii Salvii, Holmiae.

Linnaeus C 1766 - Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species cum Characteribus, Diferentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Duodecima - Laurentii Salvii, Holmiae.

Lyon MW Jr 1906 - Description of a New Species of Great Anteater from Central America - Proceedings US National Museum 31: p569-571.

Matschie P 1894 - Die von Herrn Paul Neumann in Argentinien Gesammelten und Beobachten Säugethiere - Sitzungsber. Gesells. Naturf. Freunde Berlin 1894: p57-64.

Medri IM, Mourão GM, Harada AY 2003 - Dieta de Tamandua-Bandeira Myrmecophaga tridactyla no Pantanal da Nhecolândia, Brasil - Edentata 5: p29-34.

Möller-Krull M, Delsuc F, Churakov G, Marker C, Superina M, Brosius J, Douzery EJP, Schmitz J 2007 - Retroposed Elements and Their Flanking Regions Resolve the Evolutionary History of Xenarthran Mammals (Armadillos, Anteaters and Sloths) - Molecular Biology and Evolution 24: p2573-2582.

Myers P, Espinosa R, Parr CS, Jones T, Hammond GS, Dewey A 2006 - The Animal Diversity Web (online). Accessed December 2007.

Neris N, Colman F, Ovelar E, Sukigara N, Ishii N 2002 - Guía de Mamíferos Medianos y Grandes del Paraguay: Distribución, Tendencia Poblacional y Utilización - SEAM, Asunción.

Nowak RM 1991 - Walker´s Mammals of the World 5th Ed Volume 1 - Johns Hopkins, Baltimore.

Osgood WH 1912 - Mammals from Western Venezuela and Eastern Colombia - Fieldiana Zoology 10: p33-66.

Parera A 2002 - Los Mamíferos de la Argentina y la Región Austral de Sudamérica - Editorial El Ateneo, Buenos Aires.

Prada M, Marinho-Filho J 2004 - Effects of Fire on Abundance of Xenarthrans in Mato Grosso, Brazil - Austral Ecology 29: p568-573.

Redford KH, Eisenberg JF 1992 - Mammals of the Neotropics: Volume 2 The Southern Cone - University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Rehn JAG 1900 - On the Linnean Genera Myrmecophaga and Didelphis - American Naturalist 34: p575-578.

Rocha FL, Mourão G 2006 - An Agonistic Encounter Between Two Giant Anteaters (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) - Edentata 7: p50-51.

Shaw JS, Machado-Neto JC, Carter TS 1987 - Behaviour of Free-living Giant Anteaters Myrmecophaga tridactyla - Biotropica 19: p255-259.

Thomas O 1911 - The Mammals of the Tenth Edition of Linnaeus; An Attempt to Fix the Types of the Genera and the Exact Bases and Localities of the Species - Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1911: p120-158.

Utrera A, Ramo C 1989 - Ordenamiento de la Fauna Silvestre de Apuroquia - Biollania 6: p51-76.

Villalba R, Yanosky A 2000 - Guía de Huellas y Señales: Fauna Paraguaya - Fundación Moises Bertoni, Asunción.

Widholzer FL, Voss WA 1978 - Breeding the Giant Anteater Myrmecophaga tridactyla at Sao Leopoldo Zoo - International Zoo Yearbook 18: p122-123.

Wied-Neuwied MP zu 1826 - Beiträage zue Naturgeschichte von Brasilien. Verzeichniss der Amphibien, Säugthiere un Vögel, welche auf einer Reise Zwischen dem 13ten dem 23sten Grade Südlicher Breite im Östlichen Brasilien Beobachtet Wurden II Abtheilung Mammalia, Säugthiere - Gr. HS priv. Landes Industrie Comptoirs, Weimar.

MAP 2:

Myrmecophaga tridactyla

| SKULL 2 |

|